Years ago, in patent law, the concept of “reduction to practice” had two meanings — “actual” or “constructive” reduction to practice. Whichever choice was made, “reduction to practice” was a requirement for successfully obtaining a patent. Technically, the requirement still exists. But, as discussed below, this “requirement” is now wholly met by filing a patent application. As such, the “requirement” that an invention be reduced to practice has no real meaning anymore.

The distinction between “actual” and “constructive” reduction to practice was important under the old patent regime when the United States operated under first-to-invent rules. Reducing the invention “to practice” was an important factor in determining who was first to invent — that is, who had the priority between competing inventors. The date that an invention was reduced to practice was also relevant to whether third-party publications and disclosures could be considered prior art.

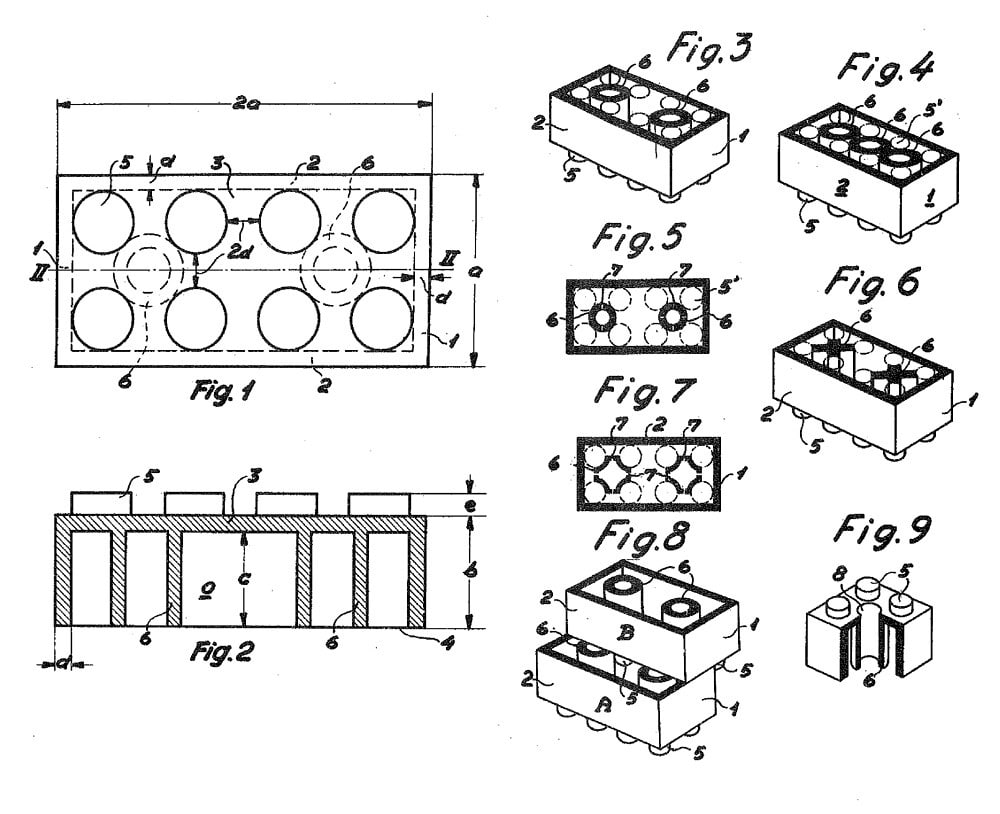

With respect to “actual” reduction to practice, an inventor was required to create an actual, practical, real-world rendition of the patentable invention into a working prototype, physical form or process. If, for example, the invention was a machine or device of some sort, then “actual” reduction to practice meant creating the machine or device in physical form. Or, if the invention was a process that was meant to make something, then “actual reduction to practice” meant establishing the process and actually creating whatever the process was intended to create.

Under the actual reduction rules established by the US Patent Office, the physical prototype or the process actually had to be created and had to function as intended. For example, if the invention was a process, it was not enough to show that the process was performed. It had to be shown the process was performed and that the intended results were accomplished. Testing was often required to prove that the invention worked and worked as intended.

By contrast, “constructive” reduction to practice involved the filing of a patent application. For the US Patent Office, filing of a patent application was — and is — deemed a sufficient reduction to practice as long as certain conditions are met. Essentially, the written descriptions and art contained in the patent application had to sufficiently disclose the invention so that a person skilled in the art and learned in the relevant field of endeavor would know how to use the invention or how to make whatever the invention was intended to make. Of course, the invention also had to meet the other requirements of patentability such as novelty and utility.

Under the old first-to-invent system, there were disputes between competing inventors with respect to who was truly the first to invent and, therefore, who was truly entitled to the protections afforded by obtaining the relevant patent. Often these disputes were between the inventor who created a prototype — actual reduction to practice — and the inventor who filed the patent application — constructive reduction to practice. In this regard, legally, there was “value” in creating a prototype since, often, a real-world prototype comes into existence before a patent application is filed.

However, these legal distinctions became moot when the United States moved from a first-to-invent patent system to a first-to-file patent system. This occurred with the passage of the American Invents Act in 2011. Under the new rules — which become effective in 2013 or so — creating a prototype or an actual reduction to practice does not provide any legal benefits with respect to patent priority. Thus, whether to create a prototype is now determined based on practical and business considerations.

For more information or if you have an invention that you want to patent, contact the patent lawyers at Revision Legal at 231-714-0100.