One thing attorneys may not learn in law school is that there are a lot of scumbags in the world. If you are lucky, a scumbag will let you know their character immediately. In other cases, even the most jaded cynic can be caught off guard.

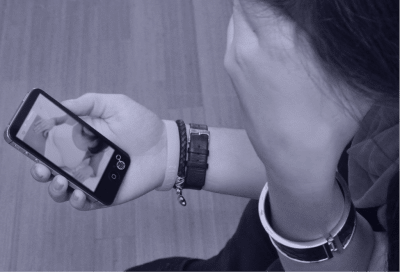

Because of the imagined anonymity of the internet and the ease of sharing videos, photos, and other information, a scumbag can invade your privacy and attempt to disrupt your life in several ways. One of the most disgusting invasions of privacy is often referred to as “revenge porn”. That term is inaccurate. We will refer to this insidious reversal of intimacy or invasion of privacy as “nonconsensual pornography” for the remainder of this article.

Nonconsensual pornography may be distributed by someone the victim knows and trusts, but it is increasingly spread by someone who surreptitiously gained access to the victim’s electronic devices to steal intimate information, often photos or communications. Such scumbags are sometimes motivated by greed, blackmailing their victims, but they might also have almost no apparent motivation. The lack of an obvious motive and the subversion of trust make nonconsensual pornography a virulent attack. We have brought cases on behalf of many clients, from all walks of life, who have found themselves victimized by someone spreading nonconsensual pornography.

In our view, our clients cannot be made whole again. It is impossible to undo the trauma and other damage many of our clients have suffered. What we consistently can do is curb the spread of nonconsensual pornography, identify the source, and make the scumbag pay monetary damages in a meager attempt at repairing the damage the scumbag has caused. When we are litigating other cases, like a copyright dispute, there are often reasonable arguments in favor of both sides. That does not happen with these cases. When we identify a scumbag, we do everything in our power to put the screws to him. Let us not pretend that “scumbag” is a gender-neutral term. In our experience, the scumbag has always been a man. In some cases, it is a male agent working for a corporate entity that should have prevented the invasion of privacy, such as an internet service provider (ISP) or a cell phone service provider. In yet other cases, the scumbag is someone in a position of authority, like a police officer, abusing his access to a victim’s electronic devices.

It is frustrating to see people writing about the culling of prominent male media figures accused of sexual harassment as though it is anything but evidence of an ongoing, systemic problem. Anyone working in media law who handles cases involving nonconsensual pornography will tell you, this is nothing new. In 1984, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit considered Hustler’s publication of stolen photographs. Wood v. Hustler Magazine, Inc., 736 F.2d 1084, 1085 (5th Cir. 1984). The stolen photographs belonged to a husband and wife who shot the film while bathing nude in a river. Id. The plaintiff’s neighbors stole the photographs, forged a consent form, and submitted images of the wife to Hustler with fabricated information concerning the wife’s fantasies, which published the images. Id. at 1086. The couple first learned of the publication through friends. Id. The wife received “a series of obscene telephone calls after the magazine appeared.” Id. Applying Texas law, the Fifth Circuit approved the district court’s award of $150,000 holding that the publication of the photo with the fabricated information invaded the wife’s privacy by placing her in a false light. Id. 1093.

More than three decades later, a fair number of people carry a video camera in their pockets able to upload and download video with little thought. As digital storage becomes cheaper, people archive and forget about a staggering amount of data. If you have ever done any “hard drive archaeology,” you were probably surprised at some of the artifacts you located. Because even carefully guarded machines can be compromised and people you trust to have access to those machines might prove themselves unworthy of such trust, it can be impossible to guard intimate images, video, chat logs, and other information that you might not even know exists.

On December 1, 2017, the New Yorker published an article concerning a high-profile lawsuit between an accomplished “rising young writer” and her ex-boyfriend, who claimed that he was entitled to enjoy some of the financial success of the young writer’s first novel because she had allegedly plagiarized portions of the novel from his writings. The plaintiff, who had purchased the writer’s old laptop, obtained intimate images and chat logs from the computer. During negotiations between the parties, The New Yorker reported that the plaintiff’s law firm sent the writer’s attorneys a draft complaint “that it said it was prepared to file in court if the two sides did not reach a settlement.” According to The New Yorker, the draft complaint included a section titled “[The Writer’s] History of Manipulating Older Men,” which began with “evidence shows that [the writer] was not the innocent and inexperienced naïf she portrayed herself to be . . . .” The article stated that the complaint included thirteen pages comprising “screenshots of explicit chat conversations with lovers, including [a nude photograph of the writer she sent] to a boyfriend, explicit banter with people she’d met online, and snippets of her most intimate diary entries.” An accompanying letter from the ex-boyfriend’s attorneys included even more intimate material. Shortly before the article published, the writer’s attorneys filed its own lawsuit alleging that her ex-boyfriend had abused the legal process to “extract millions of dollars by intimidation and threat.”

This dispute illustrates how a person might create nonconsensual pornography without intending to by not deleting chat logs or otherwise. It also demonstrates that nonconsensual pornography may not only be used for revenge. According to the writer’s legal team, the ex-boyfriend above threatened publication of nonconsensual pornography and other intimate details about the writer to extract money from the writer after she earned a staggering advance on her first novel. You might not have received “close to two million dollars” for your first novel, but, if you have been affected by nonconsensual pornography, you may have more options than you think.

Privacy laws differ by state, and the application of one state’s laws over another can profoundly affect the outcome of a litigation. For example, some states do not recognize claims for false light invasion of privacy, which was the claim considered by the Fifth Circuit in the case discussed above. Other states have enacted legislation to protect victims of nonconsensual pornography with criminal statutes. If the material at issue was created by the victim, copyright law can be an effective way to remove material from the internet. In part, because the Communications Decency Act (CDA) largely immunizes ISPs from liability arising out of content posted by third parties using an ISP, the legal issues surrounding nonconsensual pornography online are complex. If you have been victimized, talking to an attorney who understands digital media as well as your goals can be a helpful step in understanding your options.

Amanda Osorio contributed to this article